ROB SHERMAN: Residency, 2016

I came to the Bothy on a palanquin of Quorn, wine and Pepto-Bismol, and without a single retainer, to hunt. I had been told that there were many new species as yet unknown to science endemic in the Cairngorms; that they were invitingly slow, and easy for amateurs to track. I had come to pick off individuals for my collection, truss them for display, and to spirit them back down into England.

My baggage train arrived on the Inshriach Estate in late sunshine, the first of a weekful, and I bashfully loaded it into one of the Estate’s roosting brood of Land Rovers. The chickens rumbled between my feet in a quivering chassis. The Bothy is some distance from the Farm itself, along a small rutted valley beside the River Spey, and I was whiplashed up there in the Rover by Sam and Izzy, a beamish young couple from Glasgow who had recently moved here to help on the Estate. Izzy, an artist herself, sat in the back seat cheerfully asking me about my work, shushing and restraining a clanking lei of clean pots and pans. I watched the treeline for early quarry.

When we arrived at the Bothy’s birch-stuffed hollow, Bobby from the Project was hammering long, flouncy spars of steel onto its corner-posts. There had been a fashion shoot the week before, and I was to reap the benefits of swept floors, fresh cladding and a confident fire already burning deep into the stove. Bobby showed me inside, marked the corners in which I might start baiting for specimens, warned me to get the cranky, crankless radio working under any and all circumstances, and left me to it. The car shuddered off down the slope into the valley (taking Bobby, his lengths of pine and his whining tools with him), and the moreish sound of the river percolated up into the dense sieve of bracken. It stayed there.

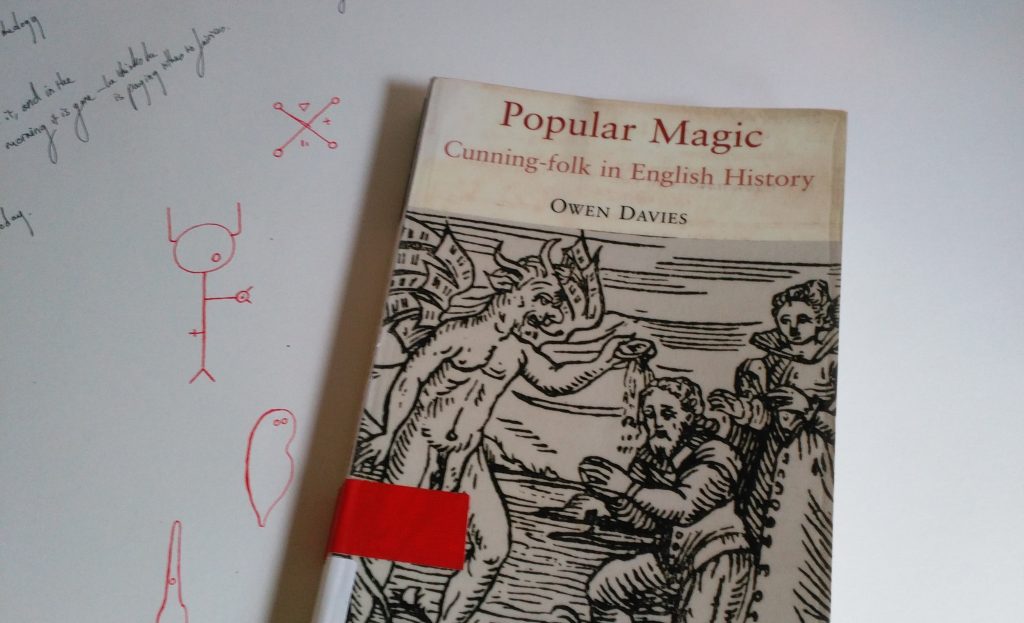

I was there, of course, to work on a project; a mixed-media installation which would tell the story of a woman called Anne Latch. Anne was a mill worker and a ‘goodcouzin’ from the village of Nighthead in Nottinghamshire who, in the summer of 1760, found an enormous and paranatural creature living in a large crack in the skirting board of her kitchen. At first she thought it was a fairy, a superstition that relatively few of her generation maintained, and latterly some affectionate, vibrant sort of Devil. Eventually she discovered that by supplicating it with certain foods, under certain phases of the moon and certain weathers and at certain times of the day, she could induce the beast to do some small things of her bidding. She named the creature Long Yocto, and took up the role of a cunning-woman; a conjurer, fortune-teller, astrologer and community magician, using her peeping familiar as a strange sort of appliance; operating it for predictions of weathers, deaths, diseases and betrayals.

Over the course of one short year she kept a bundled collection of parchment, detailing recipes, spells, manuals and accounts, documenting the uses and uselessnesses of the “half-long spyrit”. When it is finished the installation will reproduce these documents, as well as Long Yocto himself in the form of a computer simulation. Through microphones and touchscreens, sat cross-legged in the corner of a dark room masquerading as Anne’s little cottage, you will be able to care for the beast yourself; performing her rituals, divining their story and, perhaps most importantly, auguring its character.

Creating character, the simulation of beings, is very important to all my work. I think that I would be right in saying that it is important to many of the artists who have come to Inshriach Bothy. We get very anxious and bilious over the creation of ‘quality’ characters, and the definition of ‘quality’ differs from medium to medium; I work increasingly with computers, and creating characters in this way has challenges which are not shared by other, older methods. How do we judge the ‘quality’ of a character, especially when that character is not a static, unimpeachable artefact on a page or reel, but instead part of an unpredictable computer system? How can my “spyrit” be realistic, relatable, honest, vivid, thematic and humane (and whatever else we might mean by ‘quality’) when it must also contain all possible versions of itself, to be partially revealed through the whims, prods and explorations of its audience?

A skillet-grey Faraday hut in the woods, with no Internet connection and only a single, benighted solar panel to feed a table light (on a good day) seems like an odd workshop in which to address this challenge, but it was not an idle choice. My laptop and its ever-hot charger was never going to be a part of my baggage, which became more or less cake and booze all the way down. I was interested in tackling this issue without the aid (or hobbling) of a computer, and coming to the woods to approach character, to stalk it, in a different way. Here, I was approaching it sidelong, hunting for it in the dells, fens and views; hunting the wildlives of my own head. My pith was firmly on the inside.

This hunt was designed to provide evidence of my ideas; that landscapes and environments are often as characterful as those that inhabit them. As deeply complex systems of exchange and interchange, growth and decay, seasonal variation and geological integrity, natural and human places and spaces have long been individualised, venerated and personified by the people who lived in them, witnessed them or read about them. They have been positioned, in our culture, as enemies to be overcome, malicious agents, constant companions, even gods and spirits in their own right. Japan’s Mount Fuji, in the native language, is called “fuji-san”; the same honorific that is applied to other human beings. Unusually large or old trees are called ‘veterans’ in England, and are treated with as much (if not more) respect than the human elderly. The imagineering of these locales crosses cultural categories between the sciences and the arts, and it is in this metaphor, of ‘environment as character’ and ‘character as environment’, that I think I might find some help with the challenge of Long Yocto. Rather than using the heroes and villains of literature, film and the visual arts as exemplars of ‘quality’ characterisation, computer characters might instead benefit from looking to the hills, streams and woods, in which complex systems, augmented by the human imagination, grow into a form of personhood.

So, this was a tentative assaying; a smoking-out of these characters in a space far removed from the human or the metropolitan. I was here as much for the raw materials of the landscape as for the effect on my own imagination, stretched to vulnerability by a bit of isolation. With patience, some walking, some thinking and some attention, I thought that I might find a starting point for building my own landscapes; my own agent, companion and spirit.

Unfortunately, it didn’t have any of the slow, teasing plot that we have all come to associate with hunt narratives; as soon as the Rover had gone, my mental wildlife became blatant, as it always does when human beings are left on their own. I was more or less fully alone for the entire week; three days went past when I did not see any other human being, not even at a distance or in the mirror, and I was surprised that I was not more lonely. Very quickly the Bothy took on the qualities that I had imagined in Anne’s cottage; dark at night, gloomy in the day, quiet enough that I could hear the hobs and goblins in the creaks, pocked with pockets of deep cold and intense heat, spread throughout it almost phrenologically.

I washed every morning and every night in the plastic fruit bowl, hulking naked and lemon-fresh in the darkness. I looked up at the stars, and the zodiac was so obvious that I ignored it almost at once. The distant stags called day and night, steaming in heat. I found flaccid antlers, discarded and cream, lying in wrinkled fallows. At night they chuckled like Beelzebub, mooed like brontosaurs, spoke for hours. Some animal returned night after night to scrape its claws along the corrugated walls, puzzling with the zipper on my Kool-Bag. Shivering beneath four blankets I started to concoct a very detailed cosmology, relating to the cardinal direction of each window, ghosts in the woods and the alignment of the hills. I imagined a different figure appearing from the north, east, south and west, one each night, to warn me of something, and wondered what would happen on the fifth and final night.

I suppose it was no wonder that I got so superstitious, considering my reading material for the week. I read about the dead explorers scattered over Everest, serving as landmarks for later attempts. I read about Robert Macfarlane’s “mountains of the mind” (I apologise for not leaving my copy behind) and flicked through a photobook of the Cairngorms like a naturalist’s dirty calendar. I read about women like Anne, and about spirits like Yocto; about the Devil and cunning-folk and witch-bottles full of piss and nails, and dried cats wattled up in walls. Bobby had told me that the walls of the Bothy are packed with sheep’s wool, and I wondered what such benign standing spirits would protect me from. Every night I read until just before the electricity ran out, before climbing up amongst the bottles of dried Tesco herbs to the sleeping platform, dropped just below the eaves, and peered out. It was a hide looking across the marsh of my own mind.

I did not talk to myself as much as I thought I would and so every single sound I heard became an utterance. I made grass dollies and hung them on the door knobs. I ate bars of chocolate like breath mints, and put so much whiskey in my tea that it started to taste like vanilla ice cream.

I spent most of my time with the stove; resurrecting it each morning while stamping my strawberry-and-cream feet, tending it lovingly through the day, opening the hot, vented door to check on it like a rising loaf, or a clutch of chicks, or a reliquary. I read the tongues of flame licking through the vent as lips. I was so worried about having to endure a night without hot food or warmth that I fell into a fanatical series of unerring rites; the same amount of the same type of wood every single time, lit in the same places, with the same Eucharist of firelighters. When I ran out of newspaper on the penultimate day I cried for about ten minutes, but that may have been the loneliness.

I was there to divine the characters of natural landscapes, but it was that stove, and the fire that it implied, which had probably the strongest personality of anything that I encountered that week. It was right there, a tool begging to be activated, to which my relationship was rather elemental. It spoke, as all fires do, with its mouth full. Over the week I discovered its hotspots, its favourite woods, managed its tantrums and its ashen depressions. It required tenderness, and attention, and nursing, and sometimes just to be left alone. It behaved according to rules that I only dimly understood, but as time went on a consistency, a familiarity, emerged; a sort of friendship, or at least a mutual reliance, if it does not sound too bizarre. I came to love the sound of its idly pinging chimney as it cooled late at night.

I spent a lot of time like this, coming to know the character of the Bothy, and its various denizens, in the way that I had known other buildings and other appliances. It was a domestic setting that I could not ignore, and between us was precisely the sort of relationship that Anne and Yocto must have had; user and tool, owner and pet, dreamer and dream. However, I knew that I needed to occasionally slither out down the B970, stretching my half-useless legs, to see something of the landscapes that I had come so far to characterise. One day I walked fifteen miles to the edge of Glen Feshie, one of the most fondly-imagined landscapes in the world, looked in at the weather and walked home again. Another day I bypassed the deep, agate pools under Feshiebridge and returned to the Estate, where I managed about three minutes in the River Spey, acupunctured out of my wits, obliterated by the reality of it.

Another day I set out towards Loch an Eilean, before coming across a herd of deer and their orbiting stag. I was getting selfish then, after all the isolation, and I thought that it was a bit crude to actually see them up close like this; I had preferred them at a distance. But then the stag began to bellow, and stood up to reveal that he was about eighteen hands high. I scrambled up a sheer wall of rock. At the top of the hill I found a Victorian cairn, muddling obese through the trees and with a view of the Loch that was ridiculously encompassing. I had already decided on the characters of all the lochs near the Bothy from their shape and situation on the OS map; an Eilean was long and bayed, an elegant sort of place, and it looked just the same from up high. I went down to it through leg-twisting deerprints and allts hidden in the brush, and spent the rest of the day picking my way around its shores. I began to think about the arbitrary and mobile way in which the animist mindset subdivides a landscape into its constituent individuals; from the crag above the loch, the loch itself was an individual, composed of many elements in harmony. Down at the shoreline, I found an isolated castle, a perverse and marooned personality of its own. Beetles crawled painfully through the mattress of needles, iridescent and bumbling. When I stopped for a rest, I found a cracked stone which slotted into itself like a couple, like a stone knight and his wife in effigy. A shaft of sunlight illuminated a single conifer in millions, offering it up for specialty. Figures laboured on the opposite bank. The hills, as always, loomed above, starkly defined, offering up differing, vulnerable slopes of themselves as a reward for my effort.

My last trek was up the Meall Buidhe, a big yellow hill hiding between two nearer peaks, as if it was tinkering with something that it didn’t want me to see. I had glimpsed it many times in the week, and become familiar with the way the light moved across it, the starkness of the treeline, the temper of its bracken. At a human scale it was constant, immobile, but a spot of geology told you that it was really as flighty, in the long run, as any mayfly. I spent four hours climbing up into it, hauling myself close amongst its systems. I followed a gully filled with waterfalls and looming boulders forever; realised that it was this which gave the northeastern side of the hill its characteristic cleft. It was interesting how differently I felt about the hill when I was up in it, a feeling that Macfarlane articulated precisely; “when we look at a landscape, we do not see what is there, but largely what we think is there.” My own, unavoidable systems, my running nose and screaming legs and wet back, were eclipsing the mountain’s persona; its reality was quite different from what I simulated down in the Bothy. Three-quarters of the way to the top, the weather and my ankles turning, I gave up the summit as a mug’s game, thinking of the expensive logistic involved in airlifting my plaid carcass back down to sea level. On the endless, spooky logging roads back to the Bothy, in those first places from which the light disappeared, I became profoundly and spiritually uneasy. I felt evil, rank, wrong, oppressed, the trees waiting for me to trip. It was as close as I came in the week to Anne’s mindset; a rational mind beset by daily exhaustion, by a small degree of ignorance, and a world around it that seemed pregnant with encounters.

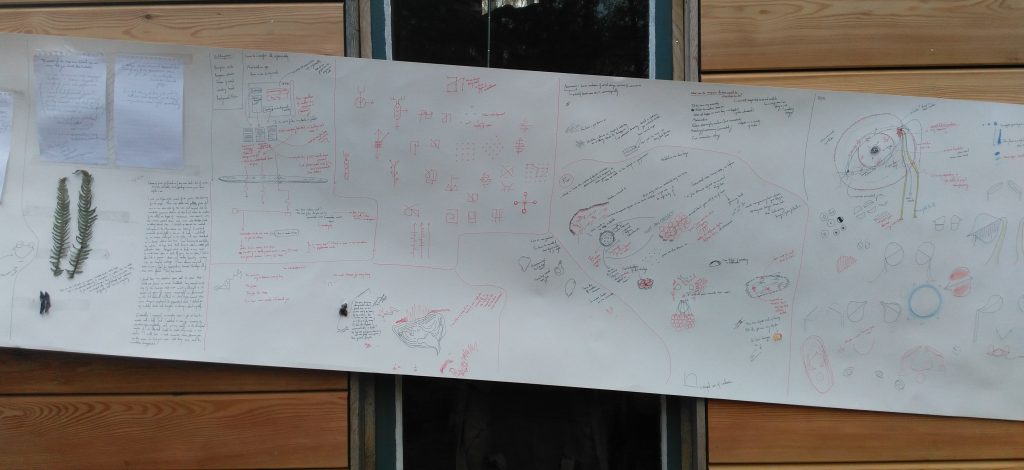

Back at the Bothy, I began the odd process of digital design without a computer. I had brought a thick roll of wallpaper lining with me, and set up the Bothy’s pull-down desk so that I could work on the scroll gradually, letting completed work drizzle to the floor on my left while unrolling fresh sections on my right. I went on like this for the entire week, smoothly, unabashedly, filling the paper with whatever I fancied. It reminded me of a film reel, or a sefer in a synagogue, or the continuous ticker tape of a Turing machine.

I became intimate with how the sun moved across the Bothy, like neighbours putting out their daily bins, and I designed a system to have an artificial sun move across Long Yocto’s face, and how he would bask in it. I designed a weather system as the wind got insistent outside. I designed Long Yocto’s eyes, how they would cry and fill with sleepydust, using the Meall Buidhe’s gullies as a template. I designed the tiny parasites that would move with their own purpose and story over his skin, copying the apparent algorithms by which the sheep in the Farm’s field clustered and flocked away from me. I wrote snatches of Anne’s speech and mores and appearance, byting her into being; I drew the magical symbols that would let her summon Yocto, and have him cure her neighbour’s cankers.

The week ended very quickly. On Saturday morning I descended the ladder as I felt I had always; I lit no fire, as I would not be there to be thick with it, like thieves. I walked the six miles, in the first real rain of the week, to Aviemore and the station. I had eaten all the Quorn, and drunk all the wine, and the light in Tescos made me squint. I was surrounded by computation once more. I smelt of chicken crisps and people avoided me. Things got both more and less complicated.

As the train hiccoughed out of the Highlands, and the phones in all the hands around me chirruped and the packaging roared and nobody at all spoke, I couldn’t tear my eye away from the window, where crowds of characters, many of which I would never come to know, saw us off with entire indifference. Grotesque mountains, elephantine with schist; suspicious forests, bristling with alert; lordly, pompous hills, wrapped in mists of state; all in diminishing heights, depths and glooms. Most people on the train around me did not look out of the window, and I imagine that it’s similar to how everybody ignores each other in big cities. If you acknowledge the tide of personality around you, you would be overwhelmed.

Soon we had reached Fife and the coast, where the sunshine hadn’t been in weeks, and the land was more like that of southeast England, where I grew up; wealdy. It is harder to characterise such landscapes, especially when you are barging through them at speed, but it is not impossible.

Past Edinburgh with its noise, and then onto Crewe with its noise, and even further south into the noise, I clutched at the specimens I had collected over the week, the castle and the stove and the stags and the parties of hills. They did not need to be dried under a lamp, or frozen into position, or fixed with a pin. They will not be labelled and placed into those darkwood cabinets which I have no room for, and into which they would never fit anyway. I never stalked to kill; only to increase the biodiversity of my mind’s reserve. They roam, they subdivide, they whelp. I purled together my understanding of how a place like the Cairngorms works, how it fits together, how its components seem to function to an observer, both up close through gasp and sandwich-breath and in repose later beside a fire, as the thing looms above and around and under you.

It remains only to thank Walter, Molly, Sam and the Inshriach Estate at large, as well as all those at the Bothy Project, for orchestrating such a glorious, and very quiet, safari.

- Inshriach Bothy

- Self-Directed Residencies 2019-2020: SOFIE LEENEN, ANNIE LORD, LAURA DAVIDSON, MARI LAGERQUIST

- THIS WAY: William Grant Foundation Residency, 2019

- VICTORIA BEESLEY: William Grant Foundation Residency, 2019

- Royal Scottish Academy, Residencies for Scotland - Bruce Shaw 2019

- LUCY WAYMAN: Bothy Project x TOAST Residency, 2019

- search the blog