Strata. “The island is pervaded by a subtle spiritual atmosphere./ It is as strange to the mind as it is to the eye. / Old songs and traditions are the spiritual analogues / of old castles and burying-places and old songs / and traditions you have in abundance. / There is a smell of the sea in the/ material air / and there is a ghostly something in the air of the imagination… / You breathe again the air of old story-books.” -Alexander Smith, ‘A Summer in Skye’, 1885

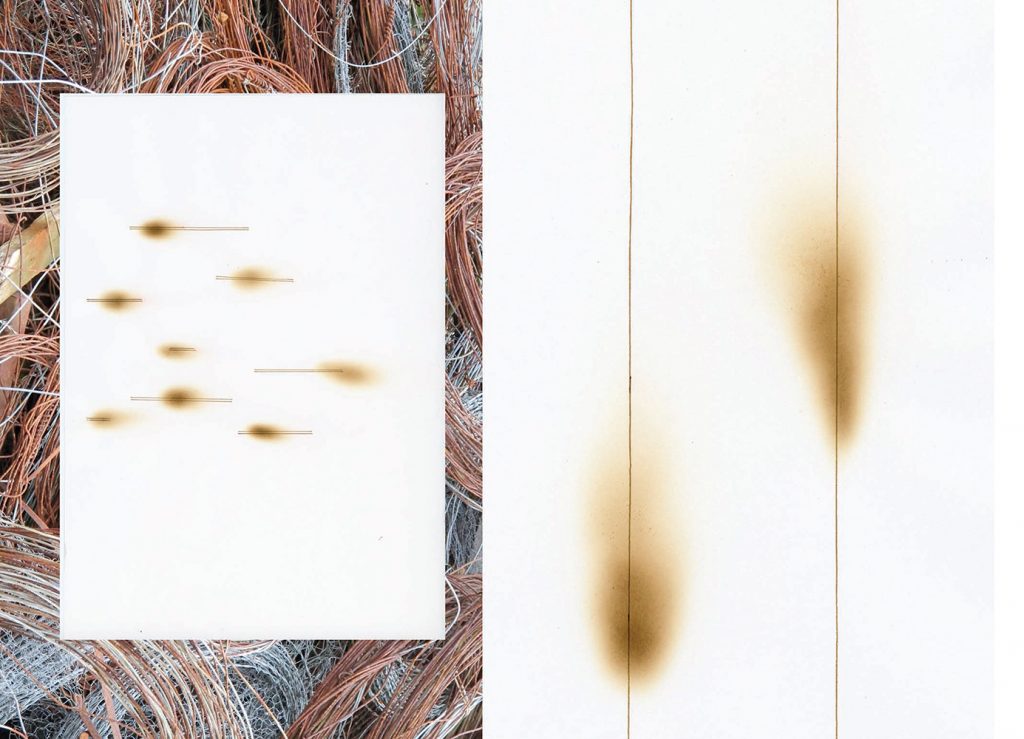

Outside of Massacre Cave on the Isle of Eigg, I refreshed my iPhone and read about the tragedy that occurred immediately in front of me. There was a longstanding clan feud that ended when a raiding party found the entire town hiding in the cave. They started a fire at the entrance and asphyxiated roughly three-hundred and ninety villagers who hid inside.

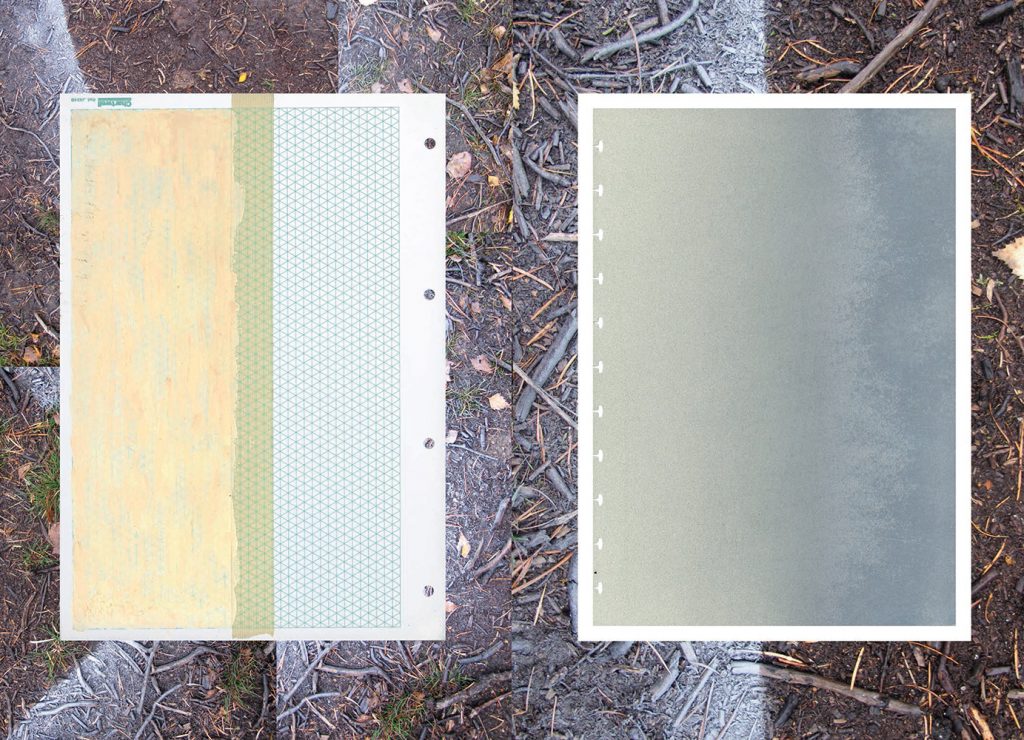

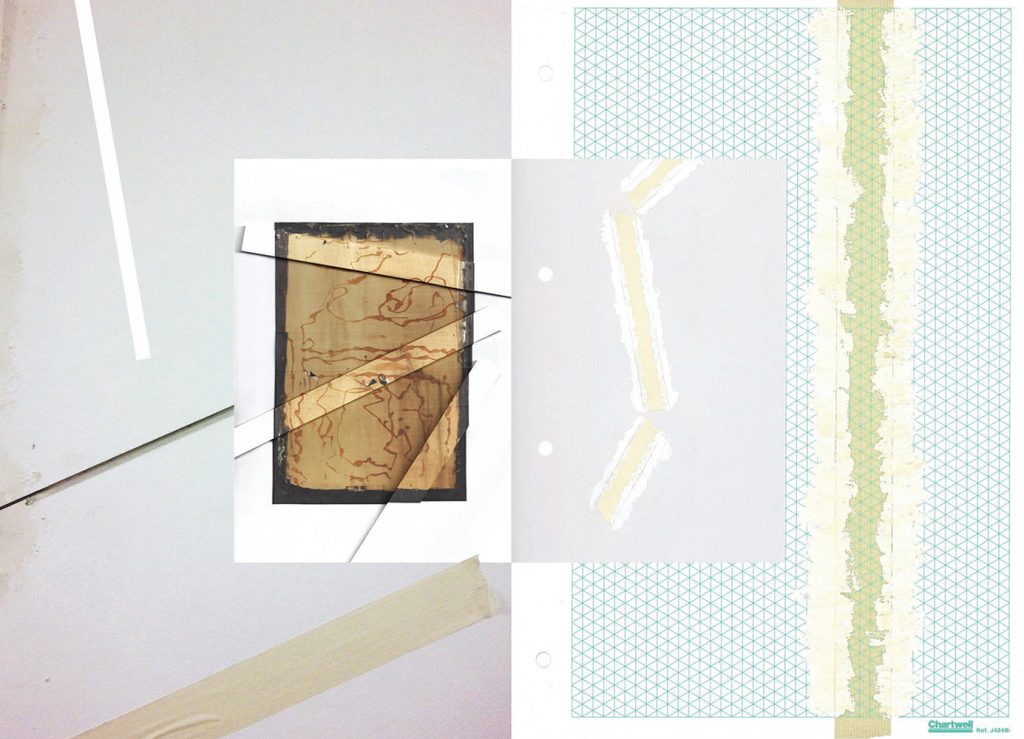

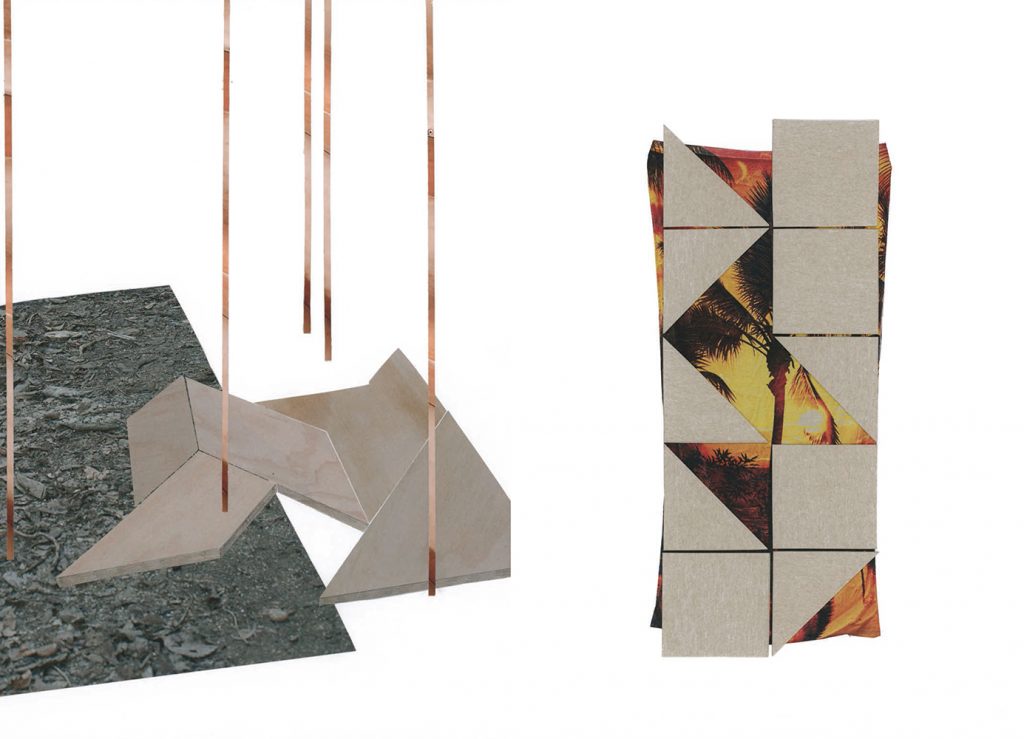

For the past year I have been photographing thresholds. On Newfoundland Island; Cape Breton, Nova Scotia; and the Isles of Skye and Eigg, Scotland. I have recorded remote, outport communities that, in the modern age of globalization, remain isolated. These islands are situated between worlds, both geographically and metaphorically. They’ve come to embody the old and the new—spaces where time collapses, where past and present collide.

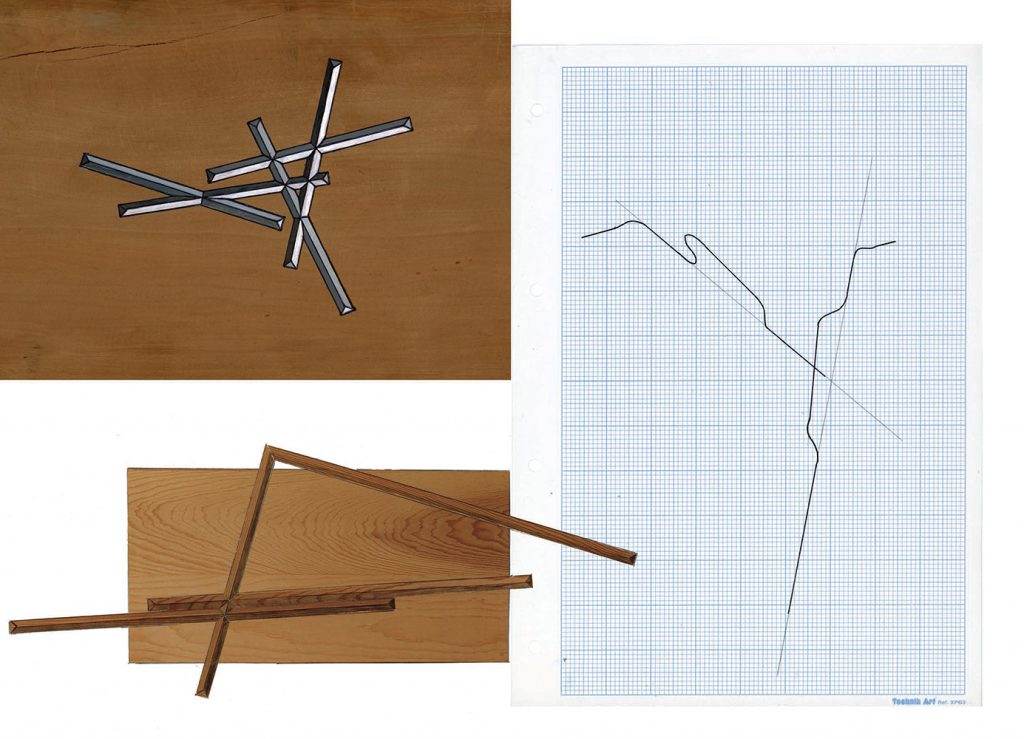

These spaces share the quality of liminality: they occupy positions at boundaries and borders; their dimensions include physical, temporal, and spiritual registers. They are property lines, rivers and bogs, lochs and ponds. Some have obvious boundaries and borders, while others are transitional and ambiguous.

On the threshold of a cave, I can sense an ancient past. “Old songs and traditions are the spiritual analogues / of old castles and burying-places.” The opposite must also be true. Caves’ rocky recesses trapped the heat of our fires. They served as our earliest shelters, our first stages, and the soot-blackened walls provided us with our first artistic canvas to depict the world around us.

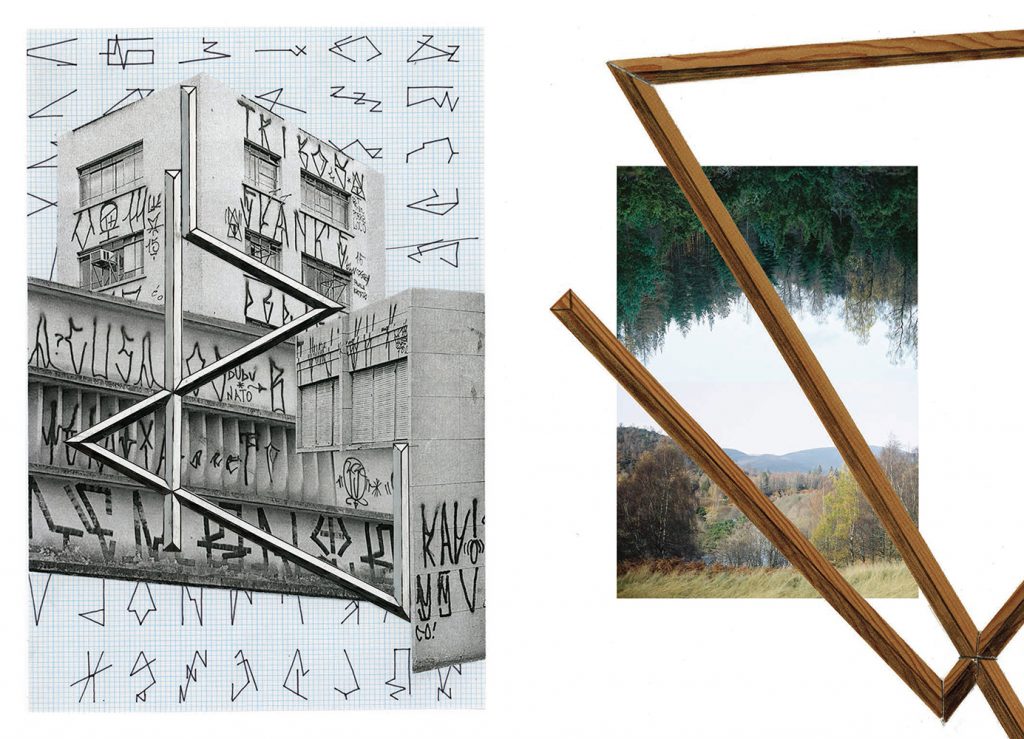

Liminal spaces disorient us. While we recognize some of these locations for their features, we sense others as a feeling, a sort of thin veil between our world and the next. We experience these feelings in isolated or remote places that instill us with fear and the sense that we aren’t welcome. These feelings are often heightened at certain times: dusk and dawn, under the glow of a full moon, or other celestial events, or during certain holidays, particularly Halloween. Liminality is a key concept in supernatural thinking, liminal times and spaces often serve as settings for supernatural occurrences in storytelling.

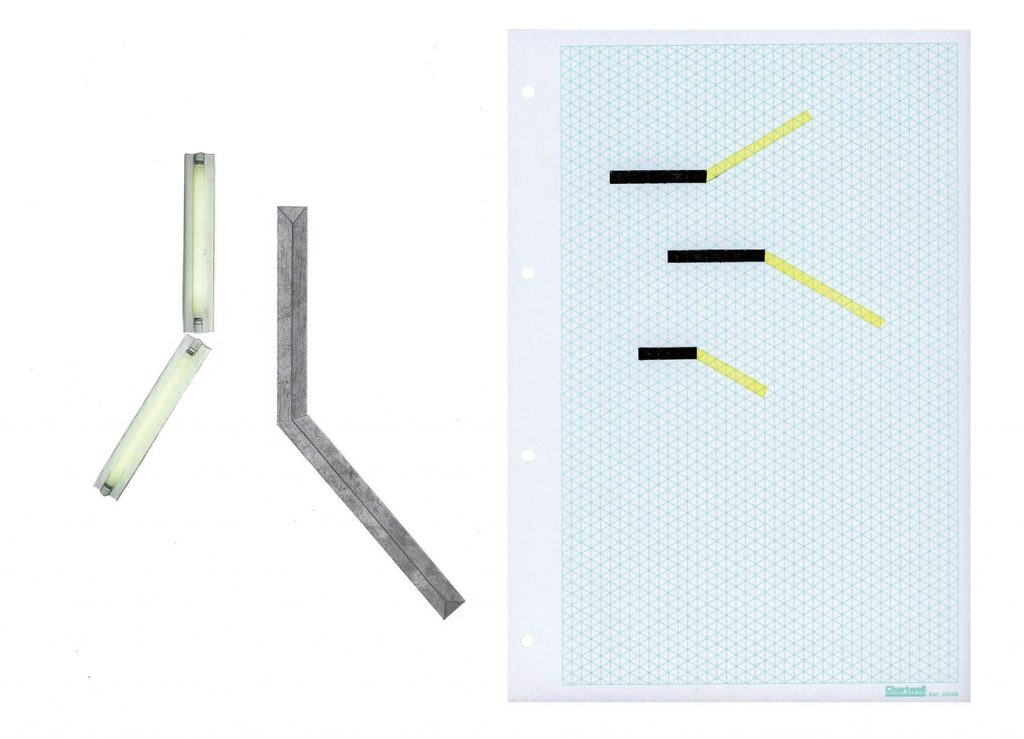

Storytelling arises out of an experience of disorientation. It seeks to explain what we cannot rationalize or understand. In a time where satellites orbiting the planet can triangulate our physical location in seconds, the experience of disorientation is more distant. My ongoing body of work explores some of the ancient sites that connect us to the past via the strange folklores, myths and legends that have been passed down. I distill history into visual elements, photographing to prompt future stories. The role of the historian or storyteller is to piece together the fragments she has, and spin them into a narrative. While I have arranged my images, my work asks the viewer to become the storyteller himself.

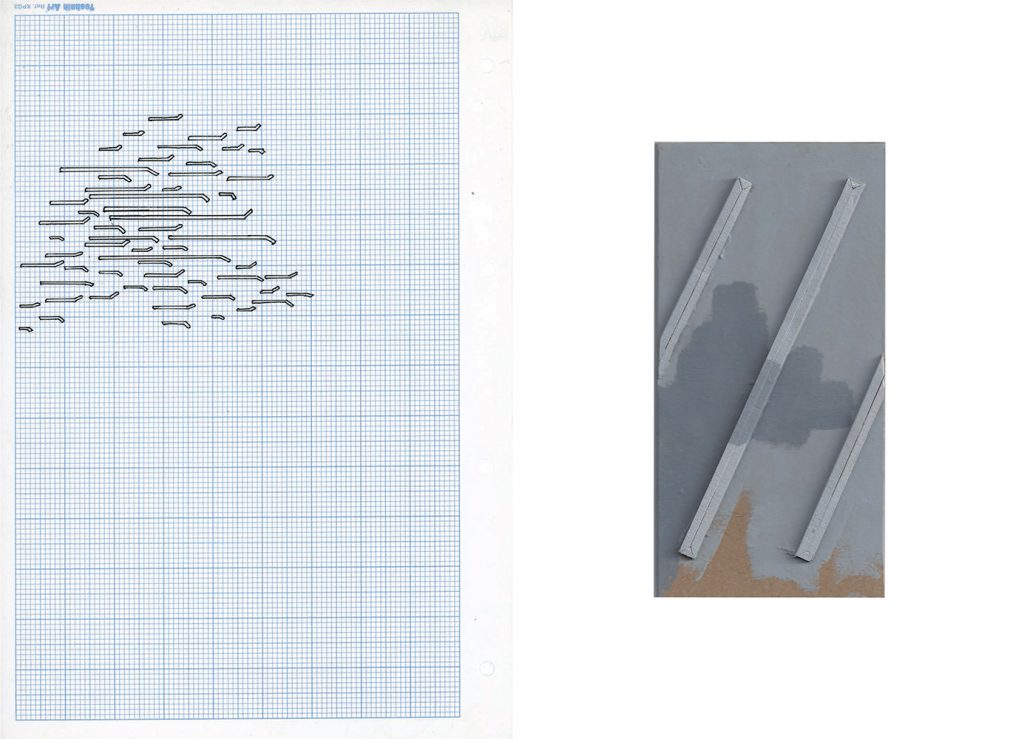

Stories relating to these liminal spaces have accumulated over thousands of years. Information packs into layers of sediment; the mineral strata describe millennia. As the most permanent surface in the natural world, rock formations carry etchings, paint, and the wear of thousands of footsteps. To the trained eye, rock faces read like sentences and paragraphs. The landscape reveals its history.

The accumulation and superposition of narratives and culture is not a seamless process. North America—where I grew up—hosts a strange and troubled convergence of societies. The people who moved here in the past 500 years have almost completely covered those who first arrived over 13,000 years ago. Indigenous Americans tell stories of creation and origin; people of European descent tell stories of exodus. Two separate histories cohabitate the same spaces.

On a planet of constant change, thresholds are inevitable. Through my work, I hope to understand and record these transitional spaces, to return to the viewer a sense of liminality, history, and disorientation, and, in the process, reopen the door to storytelling.

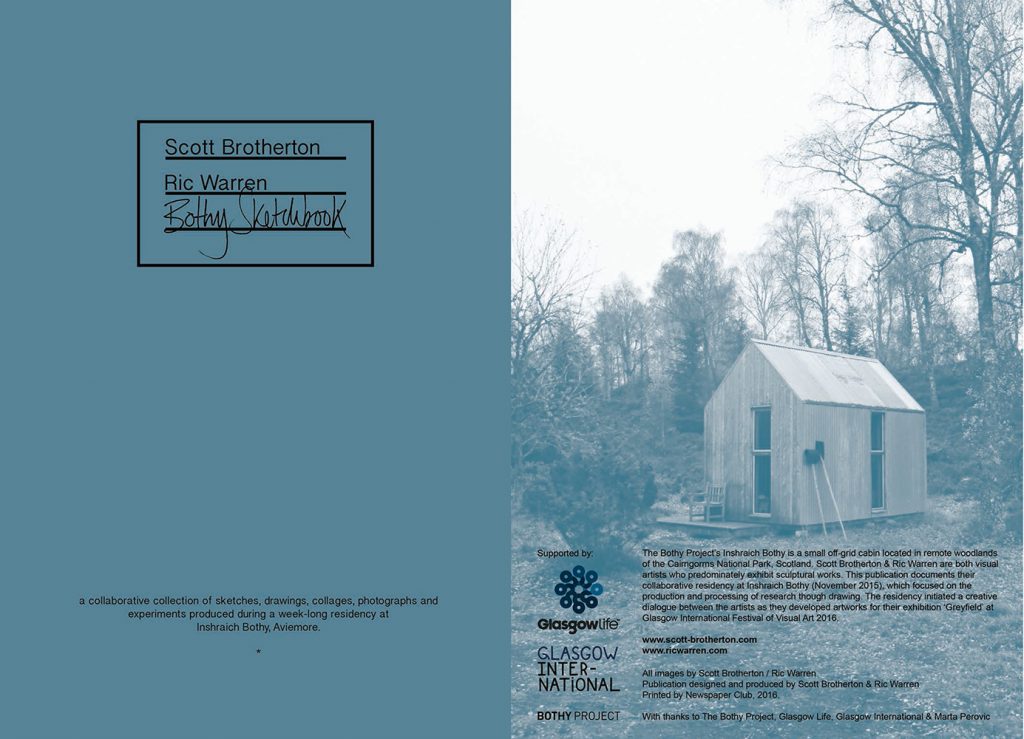

Ryan Arthurs was the artist in residence at Sweeney’s Bothy in September 2016. www.ryanarthurs.com