I stayed at the Inshriach Bothy for 2 weeks as part of the RSA Residencies for Scotland scheme. I wanted to use my time there to generate ideas for the second part of my residency at The Highland Print Studio in Inverness. I wasn’t sure what to expect from my bothy experience, and I definitely found parts of it more challenging than I’d expected. But overall it was a great experience. It’s good to go back to basics and it definitely gives you a different perspective on what’s important in life. Collecting water, chopping wood and keeping the fire going where the most essential daily tasks. Boiling the kettle felt like a big achievement!

While I was there I did a lot of reading, sketching, thinking and walking. I was also experimenting with what I could use to make my own pigments, My time in Florence last year as part of the RSA John Kinross scholarship primarily influenced my work through the simple earthy colours and terracotta all around. The bothy and surrounding woodland area were covered in autumn leaves when I arrived and had a similar tone to the colours in Italy. I was keen to incorporate the autumn colours into my own work. I collected, pressed and dried leaves with the hope of grinding them down to use as pigment at the print studio.

I was also experimenting with cyanotype prints (blue prints exposed by sunlight) as a way to potentially incorporate the leaf shapes into my prints.

The simple things in life definitely become more interesting when you don’t have technology as a distraction, and I found I really enjoyed just watching the birds while I had my morning coffee. I also decided to log my days in knitting, changing colour everyday so I could count back and see how many days I had been there.

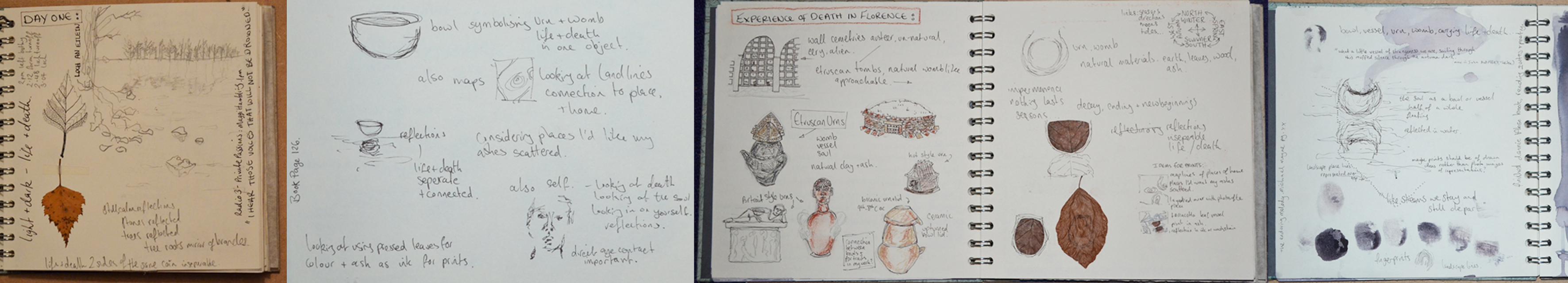

I don’t normally work in sketchbooks, instead I tend to compile loose sheets into books afterwards. However for my 2 week bothy stay I decided to use a sketchbook and log ideas, sketches and diary entries all in one book (and not rip out pages if I did a sketch I didn’t like). It helped to see clearly how my ideas changed and developed over the two weeks.

By week two the weather changed dramatically and went from autumn to winter overnight…luckily I had collected a lot of leaves in the first week as they soon disappeared under layers of snow!

With no leaves left on the trees the branches begin to reflect the shapes of veins running through the body. The links between humans and nature is something I’m interested in exploring in my work, and the way in which nature reflects elements of our lives.

“Learn how to die, and you learn how to live.”

Morrie Schwartz

This is the core idea to my research as an artist. My current practice explores the idea that by looking at death, and coming to terms with our own mortality, we are forced to really appreciate life and live it now. Through linking death, and the rituals connected to our death, with nature and an organic process, using materials such as wood and earth pigments, I aim to take it away from its stereotypical view of something scary or depressing.

“Science – scientific reasoning – seems to me an instrument that will lag far, far behind. For look here, the earth has been thought to be flat… Which however does not prevent science from proving that the earth is principally round. Which no one contradicts nowadays.

But notwithstanding this, they persist nowadays in believing that life is flat and runs from birth to death. However, life too is probably round, and very superior in expanse and capacity to the hemisphere we know at present.”

Vincent van Gogh, June 1888

Another inspiration from my time in Italy was the Etruscan tombs I visited in Populonia and the various Etruscan urns I saw in museums. Unlike the somber, eerie wall cemeteries, the Etruscan tombs were very organic in shape and colour. They had a womb like atmosphere, which helps to have a more natural acceptance of death. I started to look at creating structures or vessels with twigs which link wombs and nest shapes with the urn shapes from Italy.

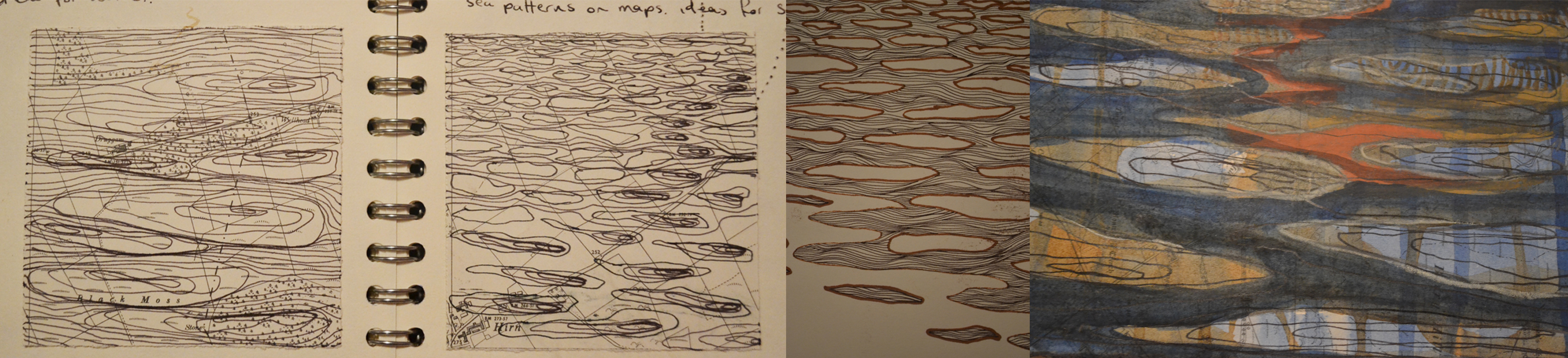

Another element of nature, which reflects life and death is the sea and I find it very interesting to try and draw the movement of water.

“The older I get I identify with the land which is being eroded…The sea is like time – you can do nothing about it. Death will come, the sea will come. It’s a metaphor for life.”

Maggi Hambling

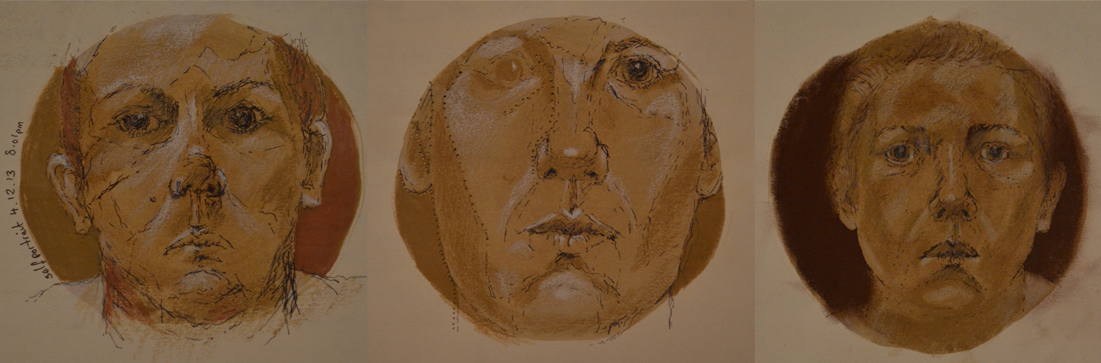

Since leaving art college I haven’t been very good at sketching regularly. However at the bothy I decided to set myself the task of doing a quick self-portrait every evening. In even a relatively short space of time I felt there was a noticeable change in my observational drawing, which made me keen to maintain my drawing skills. Like anything practice is always the best way to improve, I just need to be more focused and find a way to build it into my everyday routine now that I’m not at college anymore.

When I returned home I managed to grind the leaves down, and although it’s not a fine powder, I hope I will be able to incorporate it into a printing ink to use when I go to the print studio.

Overall I felt I had a productive 2 weeks. At times I found the darkness of winter and lack of much light in the evenings difficult. But through challenging myself in an unfamiliar environment, and limiting myself from the distractions of tv and internet, I found it much easier to think and develop ideas, which I hope to progress and turn into a body of work at The Highland Print Studio in January.